Tai Chi Principles

The Ten Essential Principles for the practice of Tai Chi Chuan by Grandmaster Yang Chengfu (1883-1936) were published in 1931. These principles formed the basis of the Yang family style of Tai Chi but also apply to most forms of Tai Chi Chuan. There is a slightly different interpretation of these principles on the Tai Chi Society website.

The 10 principles are summarised as:

- Straighten The Head

- Correct Position Of Chest And Back

- Sinking Of Shoulders And Elbows

- Relaxation Of Waist

- Solid And Empty Stance

- Use The Mind Instead Of Force

- Coordination Of Upper And Lower Parts

- Harmony Between The Internal And External Parts

- Importance Of Continuity

- Tranquility In Movement

|

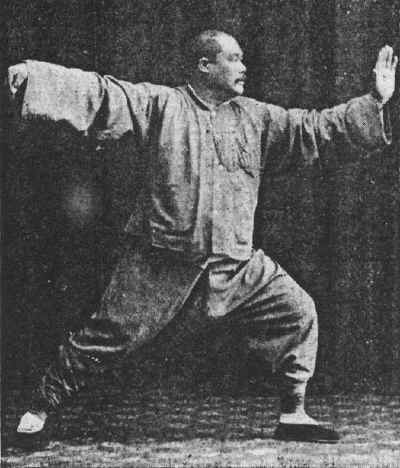

| Yang Chengfu: Single Whip |

1-5. Stance

The first 5 principles relate to physical posture or stance. These are encapsulated in the commencing posture for Tai Chi and can be summarised in the following way; starting from the feet and moving up to the head:

- Stand with feet shoulder width apart

- Feet are parallel or with toes slightly pointed out.

- Knees are relaxed and slightly bent. Weight evenly balanced over them.

- Hips and pelvis relaxed, sinking your tailbone.

- Shoulders are relaxed and back is slightly rounded

- Arms are relaxed and held slightly away from your body.

- Fingers are relaxed and in a "holding ball hand" position with fingers gently apart.

- The "Bai Hui" (crown of your head) is lifted towards the sky with your chin slightly down.

- The tip of the tongue is touching the roof of the mouth.

- Breathing is slow and down into the abdomen.

- Gaze is soft and forward or slightly down. The eyes can be closed.

6. Use The Mind Instead Of Force

In practising Tai Chi, the whole body should be relaxed. According to traditional Chinese medicine, there is a system of pathways in the human body called jingluo (or meridians) which link the viscera with different parts of the body. If the body is tense, then the jingluo is impeded and the body cannot move with ease. The movement of the body should be controlled by the mind, what the experts call "lithe in appearance, but powerful in essence". The mind directs the flow of energy and force, to the muscles and joints, not the other way around.

7. Coordination Of Upper And Lower Parts

In the Tai Chi Classics "coordination of the upper and lower body" is expressed as: "With its root in the foot, emitting from the leg, governed by the waist, manifesting in the hands and fingers". This means that a movement begins from the feet, travels up through the legs into the body and is finished by the hands.

The head and gaze generally follow the movement of the "active" hand. Each individual movement is completed in one breath, literally "one chi" where all parts of the body move together or sequentially in a combined flowing motion.

8. Harmony Between The Internal And External Parts

What we are practicing in Tai Chi depends on the spirit, hence the saying: "The spirit is the general, the body his troops." If you can combine inner and outer into a single impulse, then they become a seamless whole. The spirit or internal components are the mind, intention and energy". The external components are the shoulder & waist, elbow & knees, and hands & feet. The visible manifestations of a movement.

Each movement begins from a relaxed state as we breathe in, and then the internal components send energy into shoulders into the hips, the elbows into the knees and the hands into the feet to produce the movement and project the force. The body moves together - but not all at the same time - as the energy flows from the center out to the extremeties.

The body "opens" and "closes", when the internal forces control and direct the external "visible" forces. When one part of your body moves, every other part of your body should also be in motion; when you are still, everything should be in stillness. "Be still as a mountain, but move like a great river."

9. Importance Of Continuity

In Tai Chi, the movement from beginning to end, is carried out smoothly and ceaselessly; completing a cycle and return to the beginning, continuing endlessly. As explained in the "Harmony Between The Internal And External Parts" the body "opens" and "closes". It works like a concertina, continuously contracting and expading with only a slight pause between the two phases, between the states of "yin" and "yang".

As we breathe in and out, our body contracts and expands, gathering energy and then projecting force with intention. The movements are continuous and unbroken, not "off and on" like martial arts. This is what in Tai Chi philosopy is meant by "Endlessly flowing like the Yangtze River" or "Moving strength is like unreeling silk threads.” These both refer to unifying movement into a single impulse.

10. Tranquility In Movement

When martial artists practice where their emphasis is on speed, punching, leaping and stomping, they continue until they are out of breath and energy. In contrast, in Tai Chi Chuan we use quiescence (stillness or inactivity) to prepare for, and then produce each movement.

When you practice a form, the slower the better, using calmness and awareness. When you do it slowly your breath becomes deep and long, the chi sinks to the dantian, and there is no harmful constriction or enlargement of the blood vessels. In Tai Chi Chuan we seek stillness in movement - also known as moving meditation.